For years, she had struggled with worsening heart failure, and she was constantly tired and short of breath. She felt worn out by years of treatments and medications that hadn’t worked. Now, she was facing a critical decision: whether to undergo surgery for a heart transplant — her last option — or succumb to her failing heart.

For women in the U.S., heart disease is still the leading cause of death, causing about 1 in every 5 deaths. However, because heart research has historically focused on men’s anatomy, many women don’t receive care that’s designed for the unique ways heart disease affects them.

That’s why the UW Medicine Division of Cardiology is creating the Women’s Heart Health Initiative. Their goal is to move heart health forward by fast-tracking research, customizing care for women’s bodies and needs, and training the next generation of specialists to understand the effects of heart disease on women — like Newman.

Newman had faced many challenges, but she wasn’t done fighting. And, with help from her UW Medicine care team, she was determined to survive.

Newman was born with a heart murmur, but for decades, it didn’t seriously affect her health. An avid runner and hiker, she always enjoyed a healthy diet and active lifestyle — in part because she hoped to prevent the heart disease that ran so strongly in her family.

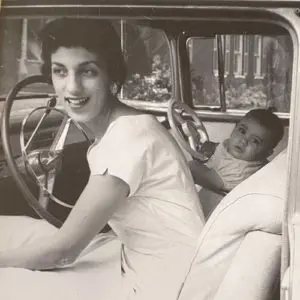

Melony Newman and her mother.

Newman’s mother, Marie, also had a heart murmur, and she experienced her first heart attack at the age of 56. For years, Newman cared for her mother through a second heart attack, a bypass and a mitral valve replacement. Finally, her doctors recommended a heart transplant, but Newman’s mother was exhausted and didn’t want to go through open-heart surgery again. Newman was just 31 when her mother passed away at age 61.

“At that time, testing and monitoring women’s heart health wasn’t routine,” says Newman. “My mother would attribute it to her generation’s lifestyle: diet, smoking and not taking care of herself. So I became almost a fanatic with healthy diet and exercise after watching what she went through. I thought and prayed that those healthy choices would prevent what happened to my mother.”

Years later, Newman’s older sister, Lory, was diagnosed with ventricular tachycardia — a serious arrhythmia that can cause sudden death or impair blood flow to the rest of the body, depending on the heart rate. Ultimately, her doctors also recommended a heart transplant in 2012, which was successful.

In 2010, Newman went to the emergency room with heart palpitations of her own. Her heart rate was over 200 beats per minute. After a week in the hospital, she received an implantable cardioverter-defibrillator (ICD), a device that detects fast heartbeats or arrhythmias and treats the condition by shocking the heart back to a normal rhythm. Like her sister, she was diagnosed with ventricular tachycardia. A few months later, she was also diagnosed with cardiomyopathy and congestive heart failure while in the hospital for heart ablation, a procedure that scars heart tissue to reduce unwanted electrical signals.

For years, Newman’s health challenges continued to worsen. She developed a progressive leak of the mitral valve, requiring surgery. At that time, her doctors suggested genetic testing.

Newman learned she had a mutation in the Lamin A/C gene (LMNA) that was responsible for her and her sister’s heart disease — and, most likely, her mother’s, too.

After the valve surgery, Newman’s health worsened rapidly. Simply walking across a room would leave her exhausted. “I would think about how much I could do, planning out my small bucket of energy,” she says.

In March 2019, Newman’s heart failure cardiologist told her she needed a heart transplant. Even after years of struggling with heart failure, it came as a shock. Newman’s last open-heart surgery had been so physically draining that, like her mother, she had sworn she wouldn’t go through it again. Reluctantly, she agreed to start the pre-testing process and join the wait list for a transplant if she was accepted.

Although Newman and her husband Jeffrey live in Oregon, there were no transplant centers in the state at the time, and they decided to travel to UW Medicine for her heart transplant. There, she met Elina Minami, MD, Fel. ’03, clinical associate professor in the Division of Cardiology.

“I knew I was in really good hands,” says Newman. “Dr. Minami has such a calm manner and an amazing and logical approach to care. She made me feel so comfortable and that I was at the right place. She is, quite simply, the most incredible healthcare professional I had ever encountered, and her focus and confidence were an inspiration to me.”

Genetic causes for heart disease, like Newman’s, are uncommon — but they are being diagnosed more and more frequently as testing improves.

“We now have the capacity to genotype over 100 genes that may be associated with the development of cardiomyopathies, and more are being identified,” says Minami. “We think about genetic causes of cardiomyopathies, particularly in younger patients with a strong family history who develop heart failure without a clear cause.”

Knowing Newman’s genetic history helped her cardiologists customize her care. Because her genetic cardiomyopathy made her higher-risk, she was prioritized for a transplant. The combination of precisely individualized care and leading-edge research is just one example of how the Women’s Heart Health Initiative seeks to improve patient care.

The initiative aims to transform women’s heart health by building upon UW Medicine’s collaborative, team-based approach. It would help cardiologists work with researchers and clinicians to better understand how heart failure and heart disease specifically impact women, and to develop treatments tailored for them. It would also help advance the research that can lead to lifesaving breakthroughs for complex heart conditions like Newman’s.

“The Women’s Heart Health Initiative is a way for us to emphasize our multidisciplinary strengths,” says Minami. “Our division has an excellent foundation providing care in the area of genetics, lipids, valvular disease, complex coronary interventions, congenital disease, arrhythmias and cardio-oncology, which drives a solid collaborative interaction with each of these subspecialized disciplines. This close relationship shapes our ability to manage our patients with precision.

“Furthermore, the division has a strong female cardiology faculty presence in all of these special niches, setting the stage to focus and think about future directions in women’s heart initiatives.”

WHO DOES THE WOMEN’S HEART HEALTH INITIATIVE AIM TO SERVE?

Everyone who identifies as a woman is welcome and supported at the Women’s Heart Health Initiative. This includes nonbinary and transgender people. By understanding and addressing the many complex ways that biological and social factors uniquely impact heart health for people who identify as women, we can improve care for all.

In June 2019, Minami decided that Newman needed an expeditious transplant evaluation because of her progressively worsening condition and arrhythmias. She warned Newman to be prepared to stay in the hospital until she was transplanted.

Newman was admitted to the hospital and listed as a candidate. In less than three weeks, a perfect donor came through. Newman is thankful that her transplant happened so quickly.

Immediately, Newman felt the difference with her new heart. “When I woke up, I remember feeling amazing inside,” Newman says. “I said to myself, oh my gosh, this is how a healthy heart feels. I couldn’t wait to tell Jeff and others. Before, my heart would flip-flop or feel like puzzle pieces that weren’t fitting. But after the transplant, it felt like how it was supposed to feel.”

Despite some side effects from surgery and medications, Newman’s recovery has made steady progress. She says she found strength in her faith as well as the love and support of her husband, family and friends.

For three months after the transplant, Newman and her husband stayed in Seattle for follow-up care and testing. Even after they went home to Oregon, Newman insisted on returning to UW Medicine — and Minami — for her long-term care.

“We both feel so comfortable with Dr. Minami and the team,” says Newman. “I was very blessed by my experience and how the team at UW Medicine focused on the ‘whole me,’ in addition to my heart.”

Support for the Women’s Heart Health Initiative will help save more lives like Newman’s. Continued research will help clinicians and scientists learn more about the genetic, biological and social factors that can influence heart disease. And by providing care that’s designed specifically for women, specialists can offer comprehensive care for even the most challenging cases.

But, says Minami, donors are an essential part of making this vision a reality.

“We have the environment and the talented scientists and physicians who provide new knowledge and commitment to excellent medical care,” says Minami. “With generous philanthropic support, we can continue advancing women’s heart health.”

That’s something Newman knows well. To commemorate her second transplant anniversary, Newman and her husband made a generous gift to support the Women’s Heart Health Initiative.

“We wanted to give back, and we wanted to honor Dr. Minami. She made a huge difference in our lives,” says Newman.

Today, Newman is looking ahead to the future. She’s taken up jogging again, goes on daily walks with their dog and enjoys watching birds and deer in their tree-lined backyard. With her newfound energy, Newman no longer feels limited in what she can do, and she’s hoping to find ways to inspire and support other patients with heart disease.

“I don’t want this to define me,” says Newman. “I wake up every day with incredible humility and joy, and I want to be able to live to the fullest now and to give back.”

Written by Stephanie Perry

If you’d like to help people like Melony receive life-changing heart health care, make a gift to the Women’s Heart Health Initiatives Fund today.