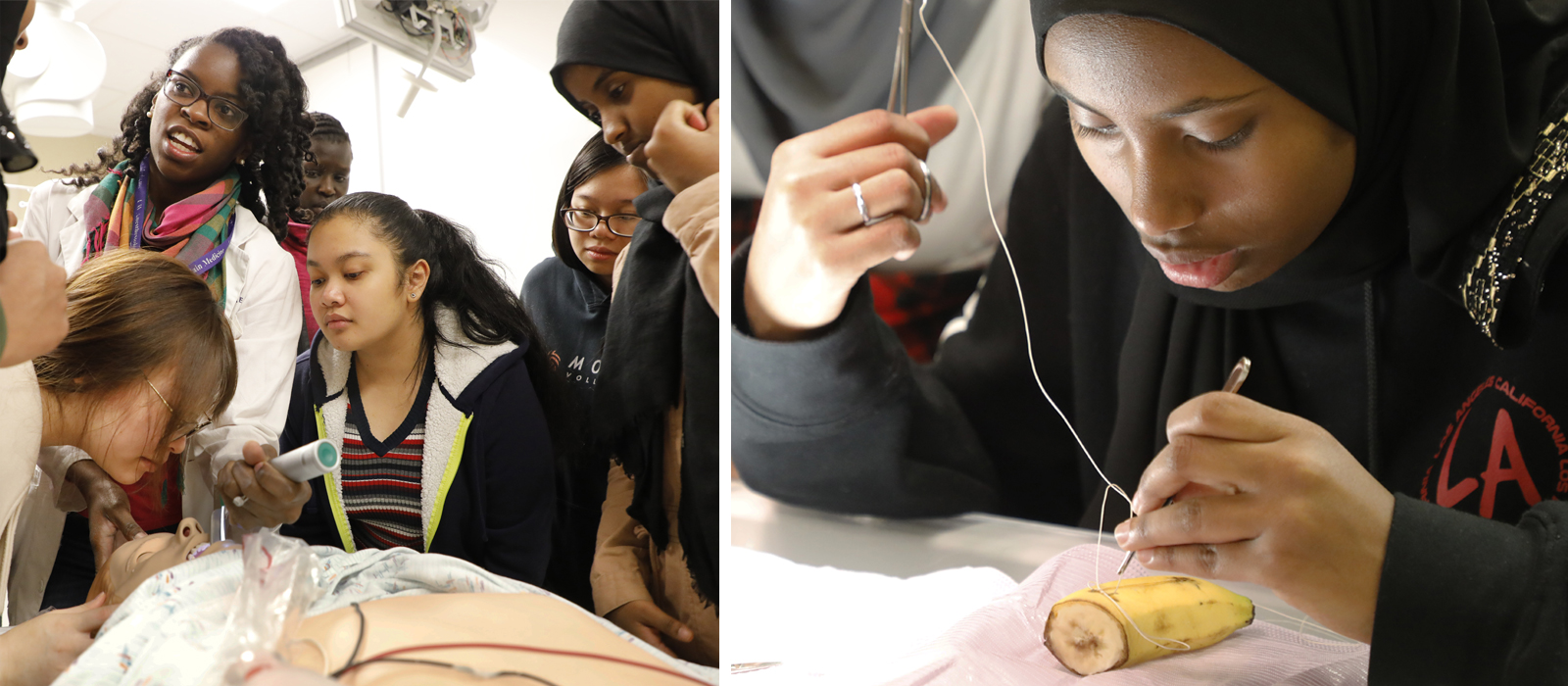

In a lab room at Harborview Medical Center, a highly perishable bunch of patients is due for surgery: about two dozen bananas with deep incisions in their skins. Students — mostly high-schoolers — are using forceps and needles to stitch each incision shut. Under the glare of the operating lights, the students frown in concentration, working carefully. A medical student shows one girl how to pull the curved surgical needle through the banana skin and adjust it with forceps. When the girl’s neighbor gets stuck a few minutes later, she turns to help her. It’s all part of Doctor for a Day — and it’s exactly what the event’s organizers wish they had had access to in their youth.

“I wasn’t the type of kid who wanted to be a doctor when I grew up — that’s not something I really thought of doing,” says Joy Thurman-Nguyen, M.D. ’17, founder of Doctor for a Day. “Growing up in Seattle and only being exposed to white medical providers, it just was not a role I saw myself in.”

Doctor for a Day (DFAD) is a youth outreach program that helps high-school and middle-school students of color learn about careers in healthcare. The program, founded by Thurman-Nguyen, is organized by medical students — assisted by Danielle Ishem, MPA, MPH, of the School’s Center for Health Equity, Diversity & Inclusion, and the program’s executive director, faculty member and surgeon Estell Williams, M.D. ’13. Their vision is to bring a hands-on, educational day of activities to students of color, featuring role models — volunteer doctors, physical therapists, nurses and dental students — who look like them.

“This is around the time that kids are really starting to think about what they can see themselves doing, so we want them to see that there are people who look like them in these jobs,” says Thurman-Nguyen.

The events take place about 10 times a year, at Harborview Medical Center, UW Medical Center and other locations around Seattle. It’s important to the student leaders that they bring their programming into the communities they’re hoping to reach, so they also connect with local high-school counselors and advisors to recruit attendees.

A typical event includes demonstrations of ultrasounds and intubation, patient interviews and an anti-smoking session featuring an inflated pig lung. There’s also a lively Q&A panel where kids can ask the volunteers about their own paths to medicine. Their questions are focused and pragmatic: How did you pay for it? Can you begin with community college? Can you take a year off between undergrad and medical school? The volunteers’ replies are frank and reassuring, underlining their belief in the students asking the questions.

Thurman-Nguyen, a family medicine resident at Kaiser Permanente, is still involved, but the program is now run by first- and second-year medical students like Naomi Nkinsi.

Nkinsi, now in her first year of medical school, remembers how an undergrad youth science program set her on the path to medicine. She believes that encouraging underrepresented students to consider healthcare careers benefits everyone in the community.

“Physicians are told to do no harm, but I think by not having this demographic of students in the classroom or the clinic, we really are doing harm to patients — not just patients of color, but the general population,” she says. “When you don’t have everyone at the table to bring their perspective, you’re doing everyone a disservice.”

As the day wraps up, the students proudly pose for Polaroids of themselves wearing white coats and stethoscopes. Some of them will return for another Doctor for a Day event, even if it has the same curriculum, simply because they enjoy it so much.

“More than anything, what I want the students to take away is that they’re capable of following this path, and they’re not alone,” says Nkinsi. “If you have other people who have already tread the path, it’s easier to follow in their footsteps.”