At Harborview Medical Center, volunteers sit with the dying — and it changes lives.

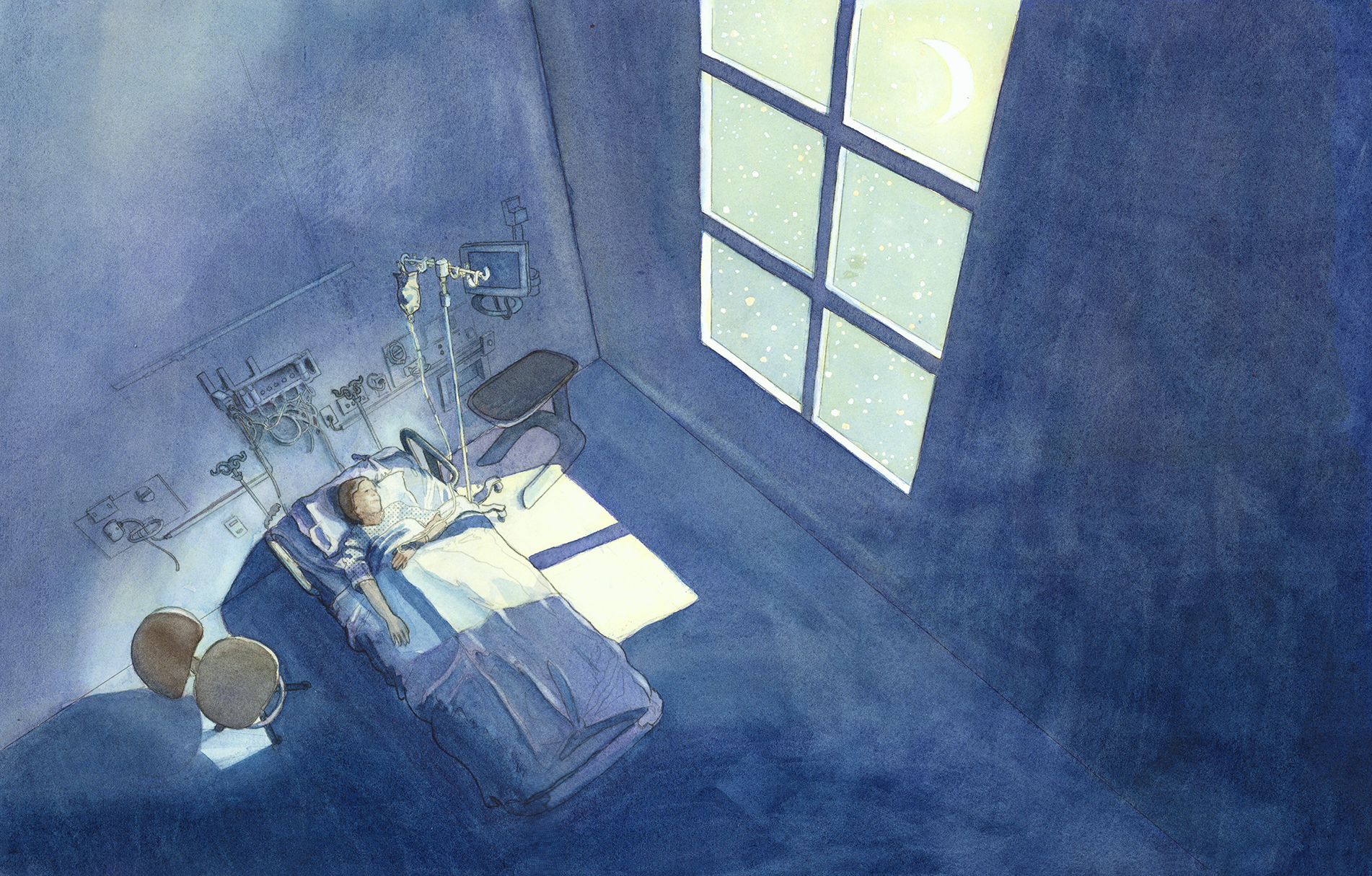

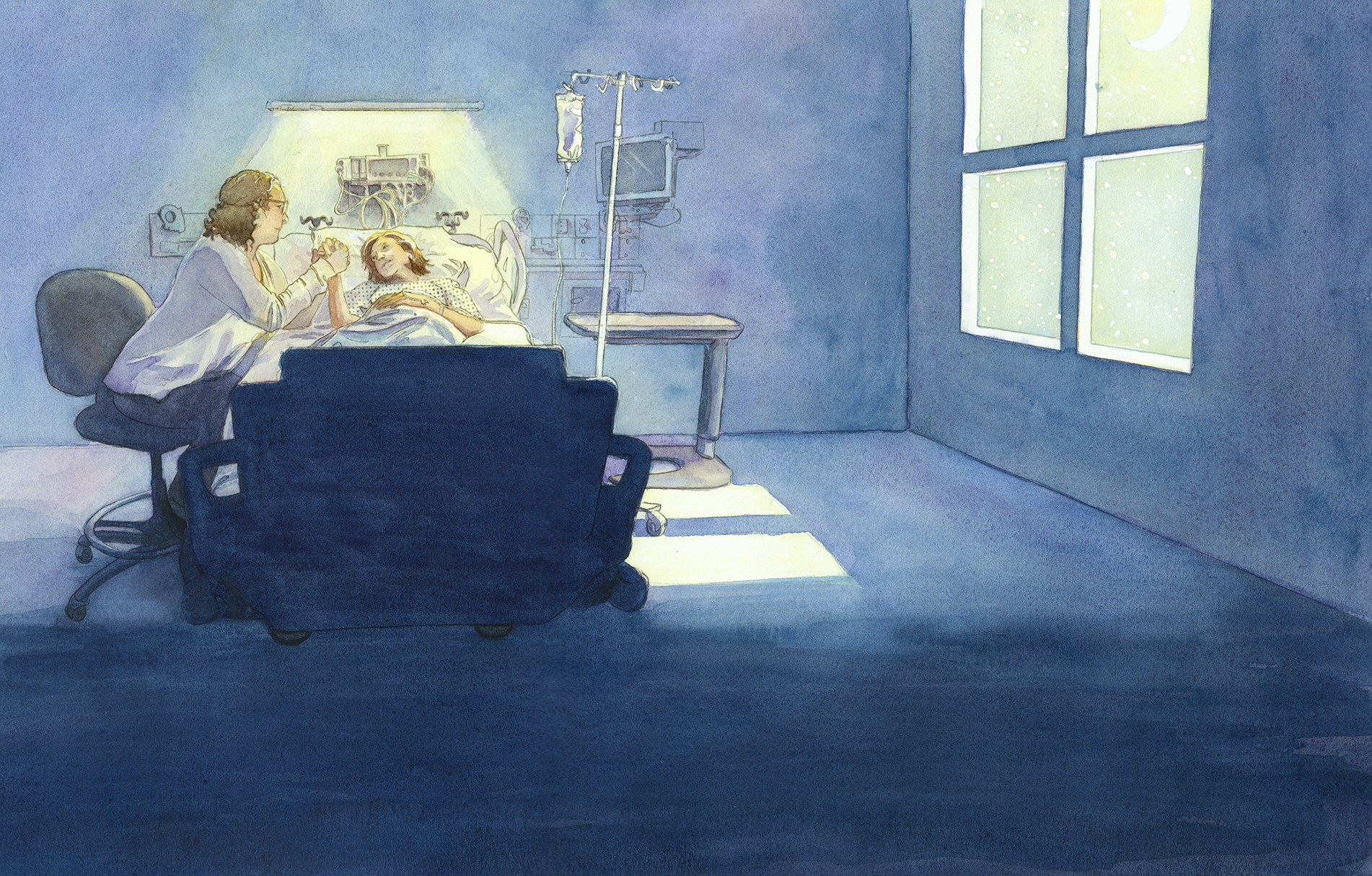

A patient is dying. In her hospital room, doctors and nurses come and go. Still, she’s mostly alone — no family and no friends to fill the room with their presence, or to bring flowers and cards. But then a visitor arrives, pulling a chair up to the bed and introducing herself.

This close to the end — it’s a matter of days now, perhaps hours — the patient is past words, but the comfort of touch endures. So the visitor takes her hand, and offers some quiet, reassuring words.

“As the body shuts down, the material world starts to fade away, and what’s precious to the person is human companionship,” says Ann Patnaude, a volunteer with No One Dies Alone (NODA), a program offered by the Department of Spiritual Care at Harborview Medical Center.

Patnaude began volunteering at Harborview by visiting Catholic patients, offering them Holy Communion and prayer. But being a volunteer for NODA, she says, offers a unique opportunity for human connection.

“Holding hands or looking into each other’s eyes — just being present is what brings a patient comfort,” says Patnaude.