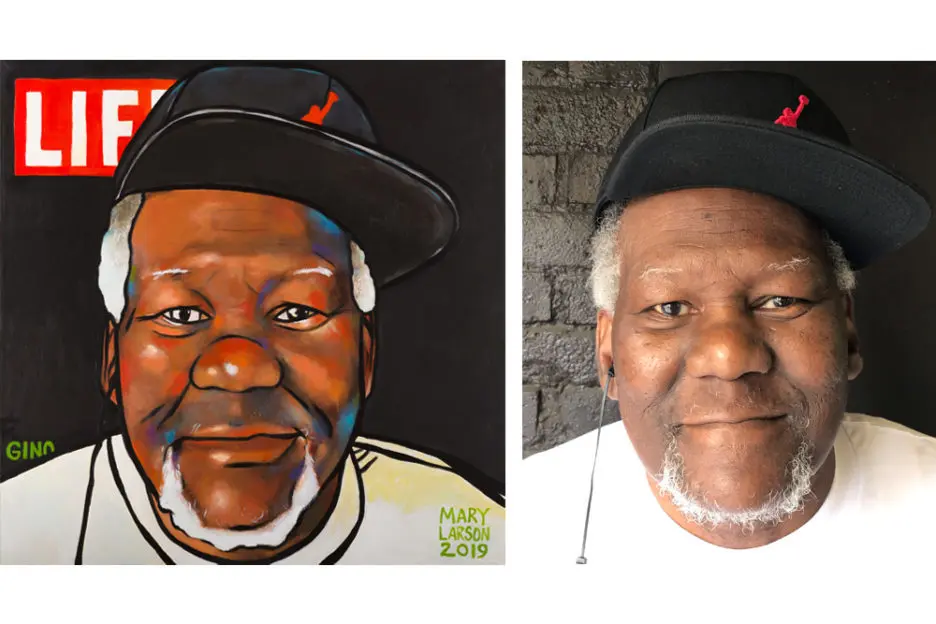

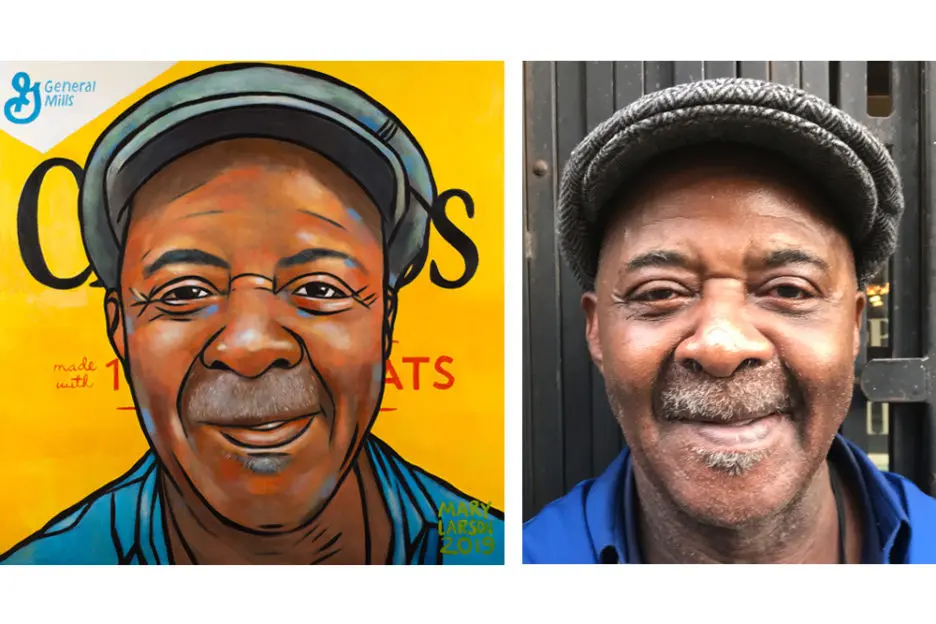

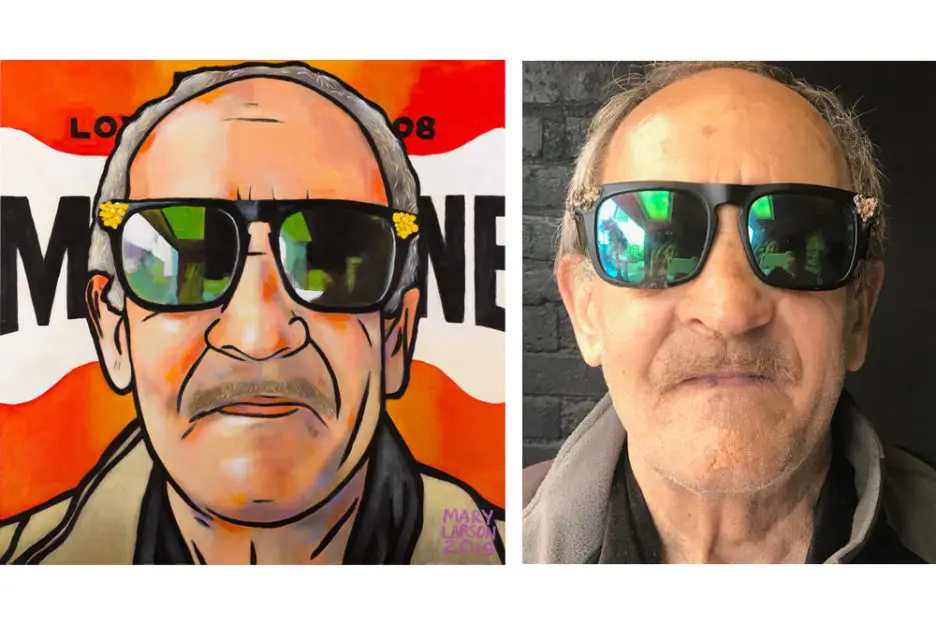

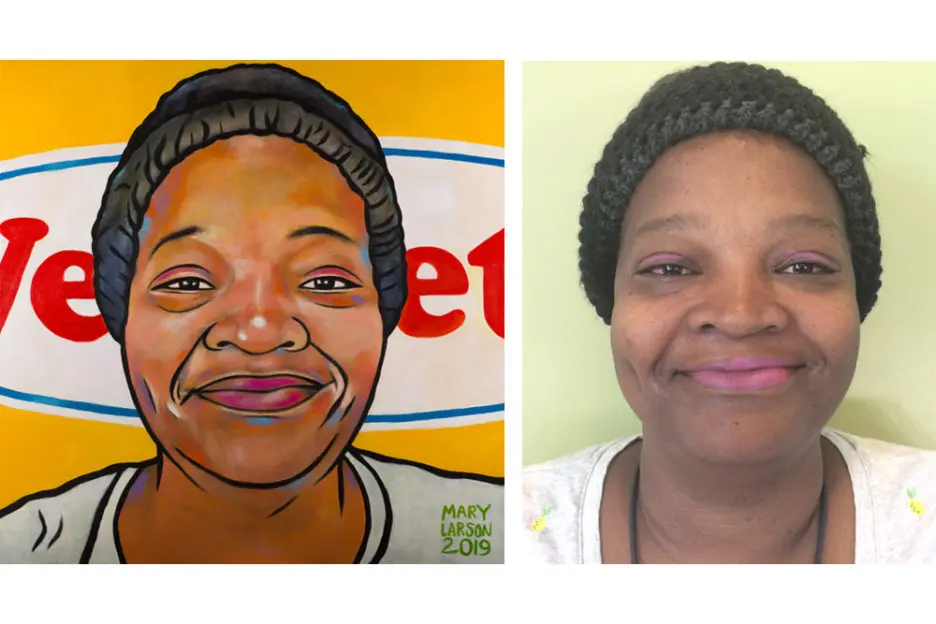

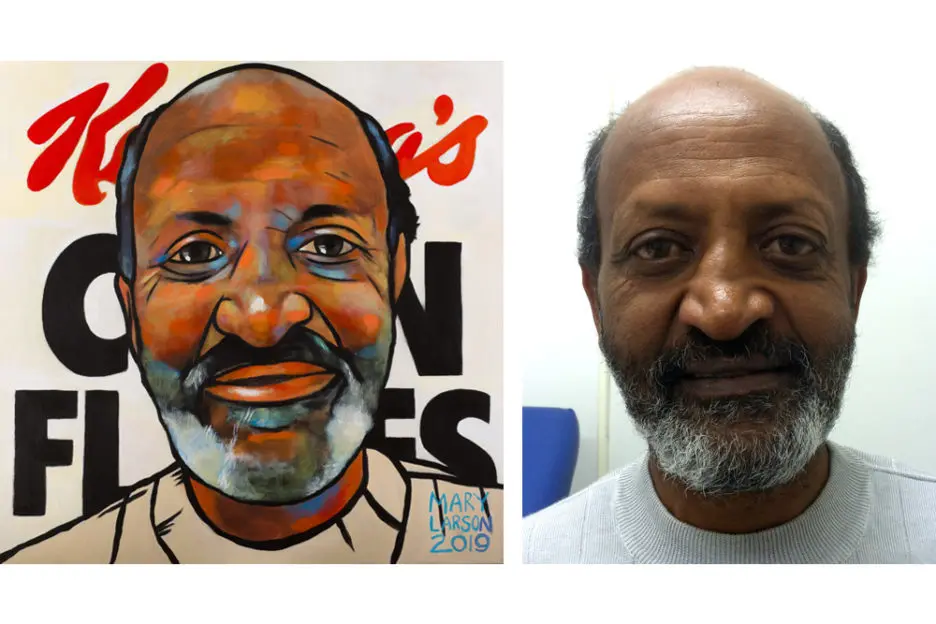

Becoming a work of art

How small is Mary Larson’s studio? So small that it’s hard for two people to stand side by side without touching. There are bookshelves, pots of acrylic paint and jars full of spiky paintbrushes. There are windows along one wall. There are also twinkle lights strung up to illuminate the space because Larson — who works at Harborview Medical Center’s Pioneer Square Clinic — sometimes gets up before dawn or stays up late to paint.

Oh, and then there are the canvases. About 12 of them. Mostly blank. And photos of people, too; Larson, a portraitist, works from photos.

“Everyone that I photograph, I ask them to tell me one thing,” says Larson. “Tell me one thing that you want people to know about you when they look at your painting.’”

It’s a powerful request for the people she’s painting. Because the people she paints — people served by the clinic, people experiencing homelessness — too often feel overlooked by society.